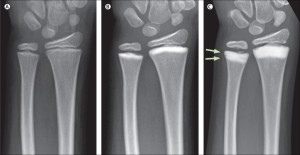

I wrote more about Cilia and the growth plate here. By understanding the growth plate response of load we can understand how LSJL influences growth plate development and how crucial it is to have a growth plate in place for LSJL to work. This study provides evidence that the adaptation to LSJL is atypical to normal load on the growth plate.

The growth plate’s response to load is partially mediated by mechano-sensing via the chondrocytic primary cilium.

Growth Plate Cilia<-link to pdf

“Chondrocytes sense and respond to mechanical stimulation. The primary cilium has been identified as a mechano-sensor in several cell types, including renal epithelial cells and endothelium, and accumulating evidence connects it to mechano-transduction in chondrocytes. In the growth plate, the primary cilium is involved in several regulatory pathways, such as the non-canonical Wnt and Indian Hedgehog. It mediates cell shape, orientation, growth, and differentiation in the growth plate. Mechanical load enhances ciliogenesis in the growth plate. This leads to alterations in the expression and localization of key members of the Ihh-PTHrP loop resulting in decreased proliferation and an abnormal switch from proliferation to differentiation, together with abnormal chondrocyte morphology and organization. We use the chondrogenic cell line ATDC5, a model for growth-plate chondrocytes, to understand the mechanisms mediating the participation of the primary cilium, and in particular KIF3A, in the cell’s response to mechanical stimulation. This key component of the cilium mediates gene expression in response to mechanical stimulation.”

“The primary cilium is critical to skeletal development; the embryonic cilium plays a role in the earliest cellular determinative events establishing left–right axis asymmetry and primary cilia in the early mesenchyme is necessary for proper anterior-posterior limb patterning”

“the primary cilium is required for bone cell response (increase in the expression of osteopontin) to dynamic fluid flow”

“The primary cilium mediates cell shape, orientation, growth, and differentiation in the growth plate as deletion of KIF3A, a subunit of the motor protein kinesin-II, results in defects in the columnar organization of the growth plate together with reduced cell division, accelerated hypertrophic differentiation, and disruption of cell shape and orientation relative to the long axis of the bone”

“Ihh, directly through its receptor Patched-1 (ptc1), increases chondrocyte proliferation and inhibits its hypertrophic differentiation through induction of Parathyroid hormonerelated

protein (PTHrP) expression”

For mechanical stimulation, cells were stetched at 1HZ by 20% elongation.

“the transition between the proliferative zone (positive for collagen II) and hypertrophic zone (positive for collagen X) was more homogeneous in the growth plates that were subjected to loading, suggesting that not only proliferation is altered by the load, but also the switch between proliferation and differentiation is altered.”<-Thus suggesting that PTH and IHH was involved. However, this was not the case with LSJL growth plates. In that study, the hypertrophic and proliferative zone was less homogeneous.

“[In loaded growth plates], cells in the proliferative zone deviated less from the center of the column compared with the control growth plates in which more cells deviated from the column line”

“Morphometric analysis showed a significant increase in the number of cells per defined area and a decrease in the average cell area”<-Both number of cells and cell area increased during LSJL loading.

“the cells in the proliferative zone were more spread out, whereas those in the hypertrophic zone were more spherical, suggesting that mechanical load affects chondrocyte morphology and organization within the growth plate.”

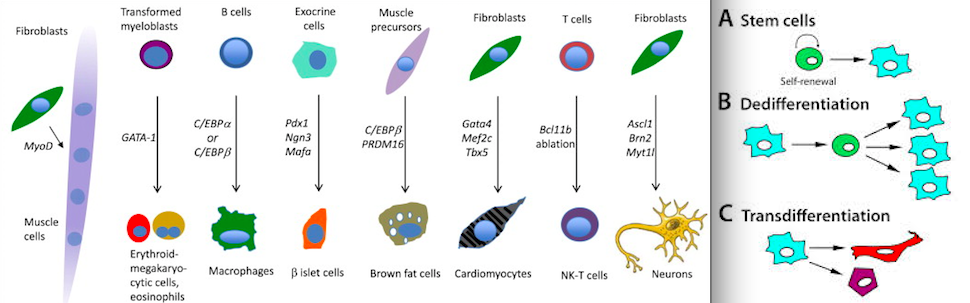

A diagram depecting a chondrocytes response to stress:

“a Unstimulated GP chondrocyte: Ihh, directly through its receptor Patched-1 (ptc1), located in the cilium, increases chondrocyte proliferation and inhibits its hypertrophic differentiation through induction of Parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) expression. b Mechanical stimulated GP chondrocyte: morphological change of the cell together with up-regulation of cilia related genes (IFT88, KIF3A, PKD1 and PKD2) and formation of stress fibers. Decrease in the expression of Ihh and ptc1 results in major decrease of PTHrP expression following reduced proliferation and switch for differentiation”

“we did not observe any significant difference in the cilia length caused by the mechanical stimulation. In all checked samples, around 80 % of the cells presented cilia (counted according to acetylated-tubulin staining in comparison to nucleus DAPI staining), and cilia length was 2.4 lM,”

“primary articular chondrocytes [were subjected] to cyclic tensile strain up to 20 % for 1 h at 0.33 Hz and primary cilia prevalence was not altered in response to this stimulation” However other studies found that cilia subjected to higher strain were reduced by 15.1%.

In this study C-Fos and egr1 were upregulated two genes that were also upregulated by LSJL.

“tensile load is induced during stretching while compression load is induced during release from stretch. Both acts induce fluid flow, thus creating shear load.”

“in control cells, mechanical stimulation induced Ihh expression, and activation of the pathway by SAG stimulation increased the expression of ptc1 and its accumulation in the cilium. Knockdown of KIF3A abolished these responses.”