Me: This is the biggest collaborative project geneticists and scientists have ever done looking at what are the hundreds of genes which do affect height which is a polygenic trait. For me, this article is a VERY BIG DEAL. Right here is the sum of the hard work done by hundreds of researchers who have all been studying to find out the genes that cause the variation in human height.

Note: If you really are serious about finding a solution I would say it is critical to look through the supplementary material which is cited at the bottom of the article. but you can click HERE for a copy of the .DOC file.

From the Nature website source link HERE.

From PubMed website source link HERE. for the actual link that I got the Full Text from click HERE.

Nature. 2010 Oct 14;467(7317):832-8. Epub 2010 Sep 29.

Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height.

Lango Allen H, Estrada K, Lettre G, Berndt SI, Weedon MN, Rivadeneira F, Willer CJ, Jackson AU, Vedantam S, Raychaudhuri S, Ferreira T, Wood AR, Weyant RJ, Segrè AV, Speliotes EK, Wheeler E, Soranzo N, Park JH, Yang J, Gudbjartsson D, Heard-Costa NL, Randall JC, Qi L, Vernon Smith A, Mägi R, Pastinen T,Liang L, Heid IM, Luan J, Thorleifsson G, Winkler TW, Goddard ME, Sin Lo K, Palmer C, Workalemahu T, Aulchenko YS, Johansson A, Zillikens MC, Feitosa MF,Esko T, Johnson T, Ketkar S, Kraft P, Mangino M, Prokopenko I, Absher D, Albrecht E, Ernst F, Glazer NL, Hayward C, Hottenga JJ, Jacobs KB, Knowles JW,Kutalik Z, Monda KL, Polasek O, Preuss M, Rayner NW, Robertson NR, Steinthorsdottir V, Tyrer JP, Voight BF, Wiklund F, Xu J, Zhao JH, Nyholt DR, Pellikka N,Perola M, Perry JR, Surakka I, Tammesoo ML, Altmaier EL, Amin N, Aspelund T, Bhangale T, Boucher G, Chasman DI, Chen C, Coin L, Cooper MN, Dixon AL,Gibson Q, Grundberg E, Hao K, Juhani Junttila M, Kaplan LM, Kettunen J, König IR, Kwan T, Lawrence RW, Levinson DF, Lorentzon M, McKnight B, Morris AP,Müller M, Suh Ngwa J, Purcell S, Rafelt S, Salem RM, Salvi E, Sanna S, Shi J, Sovio U, Thompson JR, Turchin MC, Vandenput L, Verlaan DJ, Vitart V, White CC, Ziegler A, Almgren P, Balmforth AJ, Campbell H, Citterio L, De Grandi A, Dominiczak A, Duan J, Elliott P, Elosua R, Eriksson JG, Freimer NB, Geus EJ,Glorioso N, Haiqing S, Hartikainen AL, Havulinna AS, Hicks AA, Hui J, Igl W, Illig T, Jula A, Kajantie E, Kilpeläinen TO, Koiranen M, Kolcic I, Koskinen S, Kovacs P, Laitinen J, Liu J, Lokki ML, Marusic A, Maschio A, Meitinger T, Mulas A, Paré G, Parker AN, Peden JF, Petersmann A, Pichler I, Pietiläinen KH, Pouta A,Ridderstråle M, Rotter JI, Sambrook JG, Sanders AR, Schmidt CO, Sinisalo J, Smit JH, Stringham HM, Bragi Walters G, Widen E, Wild SH, Willemsen G, Zagato L, Zgaga L, Zitting P, Alavere H, Farrall M, McArdle WL, Nelis M, Peters MJ, Ripatti S, van Meurs JB, Aben KK, Ardlie KG, Beckmann JS, Beilby JP, Bergman RN,Bergmann S, Collins FS, Cusi D, den Heijer M, Eiriksdottir G, Gejman PV, Hall AS, Hamsten A, Huikuri HV, Iribarren C, Kähönen M, Kaprio J, Kathiresan S,Kiemeney L, Kocher T, Launer LJ, Lehtimäki T, Melander O, Mosley TH Jr, Musk AW, Nieminen MS, O’Donnell CJ, Ohlsson C, Oostra B, Palmer LJ, Raitakari O,Ridker PM, Rioux JD, Rissanen A, Rivolta C, Schunkert H, Shuldiner AR, Siscovick DS, Stumvoll M, Tönjes A, Tuomilehto J, van Ommen GJ, Viikari J, Heath AC, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Province MA, Kayser M, Arnold AM, Atwood LD, Boerwinkle E, Chanock SJ, Deloukas P, Gieger C, Grönberg H, Hall P,Hattersley AT, Hengstenberg C, Hoffman W, Lathrop GM, Salomaa V, Schreiber S, Uda M, Waterworth D, Wright AF, Assimes TL, Barroso I, Hofman A, Mohlke KL, Boomsma DI, Caulfield MJ, Cupples LA, Erdmann J, Fox CS, Gudnason V, Gyllensten U, Harris TB, Hayes RB, Jarvelin MR, Mooser V, Munroe PB,Ouwehand WH, Penninx BW, Pramstaller PP, Quertermous T, Rudan I, Samani NJ, Spector TD, Völzke H, Watkins H, Wilson JF, Groop LC, Haritunians T, Hu FB, Kaplan RC, Metspalu A, North KE, Schlessinger D, Wareham NJ, Hunter DJ, O’Connell JR, Strachan DP, Wichmann HE, Borecki IB, van Duijn CM, Schadt EE, Thorsteinsdottir U, Peltonen L, Uitterlinden AG, Visscher PM, Chatterjee N, Loos RJ, Boehnke M, McCarthy MI, Ingelsson E, Lindgren CM, Abecasis GR,Stefansson K, Frayling TM, Hirschhorn JN.

Source

Genetics of Complex Traits, Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Exeter, Exeter EX1 2LU, UK.

Abstract

Most common human traits and diseases have a polygenic pattern of inheritance: DNA sequence variants at many genetic loci influence the phenotype. Genome-wide association (GWA) studies have identified more than 600 variants associated with human traits, but these typically explain small fractions of phenotypic variation, raising questions about the use of further studies. Here, using 183,727 individuals, we show that hundreds of genetic variants, in at least 180 loci, influence adult height, a highly heritable and classic polygenic trait. The large number of loci reveals patterns with important implications for genetic studies of common human diseases and traits. First, the 180 loci are not random, but instead are enriched for genes that are connected in biological pathways (P = 0.016) and that underlie skeletal growth defects (P < 0.001). Second, the likely causal gene is often located near the most strongly associated variant: in 13 of 21 loci containing a known skeletal growth gene, that gene was closest to the associated variant. Third, at least 19 loci have multiple independently associated variants, suggesting that allelic heterogeneity is a frequent feature of polygenic traits, that comprehensive explorations of already-discovered loci should discover additional variants and that an appreciable fraction of associated loci may have been identified. Fourth, associated variants are enriched for likely functional effects on genes, being over-represented among variants that alter amino-acid structure of proteins and expression levels of nearby genes. Our data explain approximately 10% of the phenotypic variation in height, and we estimate that unidentified common variants of similar effect sizes would increase this figure to approximately 16% of phenotypic variation (approximately 20% of heritable variation). Although additional approaches are needed to dissect the genetic architecture of polygenic human traits fully, our findings indicate that GWA studies can identify large numbers of loci that implicate biologically relevant genes and pathways.

In Stage 1 of our study, we performed a meta-analysis of GWA data from 46 studies, comprising 133,653 individuals of recent European ancestry, to identify common genetic variation associated with adult height. To enable meta-analysis of studies across different genotyping platforms, we performed imputation of 2,834,208 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) present in the HapMap Phase 2 European-American reference panel4. After applying quality control filters, each individual study tested the association of adult height with each SNP using an additive model (Supplementary Methods). The individual study statistics were corrected using the genomic control (GC) method5,6 and then combined in a fixed effects based meta-analysis. We then applied a second GC correction on the meta-analysis statistics, although this approach may be overly conservative when there are many real signals of association (Supplementary Methods). We detected 207 loci (defined as 1Mb on either side of the most strongly associated SNP) as potentially associated with adult height (P<5×10-6).

To identify loci robustly associated with adult height, we took forward at least one SNP (Supplementary Methods) from each of the 207 loci reaching P<5×10-6 into an additional 50,074 samples (Stage 2) that became available after completion of our initial meta-analysis. In the joint analysis of our Stage 1 and Stage 2 studies, SNPs representing 180 loci reached genome-wide significance (P<5×10-8;Supplementary Figures 1 and 2, Supplementary Table 1). Additional tests, including genotyping of a randomly-selected subset of 33 SNPs in an independent sample of individuals from the 5th-10th and 90th-95th percentiles of the height distribution (N=3,190)7, provided further validation of our results, with all but two SNPs showing consistent direction of effect (sign test P<7×10-8) (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 2).

Genome wide association studies can be susceptible to false positive associations from population stratification7. We therefore performed a family-based analysis, which is immune to population stratification in 7,336 individuals from two cohorts with pedigree information. Alleles representing 150 of the 180 genome-wide significant loci were associated in the expected direction (sign test P<6×10-20;Supplementary Table 3). The estimated effects on height were essentially identical in the overall meta-analysis and the family-based sample. Together with several other lines of evidence (Supplementary Methods), this indicates that stratification is not substantially inflating the test statistics in our meta-analysis.

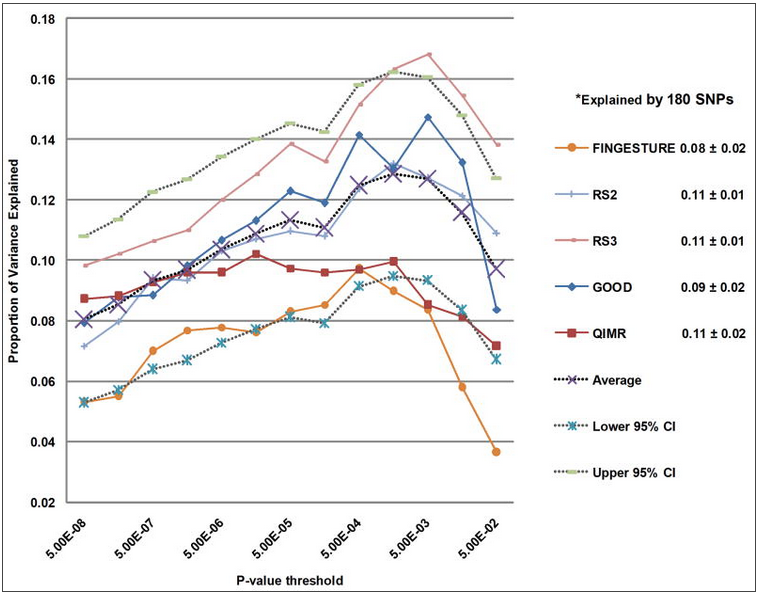

Common genetic variants have typically explained only a small proportion of the heritable component of phenotypic variation8. This is particularly true for height, where >80% of the variation within a given population is estimated to be attributable to additive genetic factors9, but over 40 previously published variants explain <5% of the variance10–17. One possible explanation is that many common variants of small effects contribute to phenotypic variation, and current GWA studies remain underpowered to detect the majority of common variants. Using five studies not included in Stage 1, we found that the 180 associated SNPs explained on average 10.5% (range 7.9-11.2%) of the variance in adult height (Supplementary Methods). Including SNPs associated with height at lower significance levels (0.05>P>5×10-8) increased the variance explained to 13.3% (range 9.7-16.8%) (Figure 1a)18. In addition, we found no evidence that non-additive effects including gene-gene interaction would increase the proportion of the phenotypic variance explained (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Tables 5 and 6).

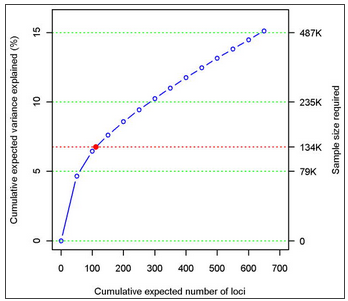

Phenotypic variance explained by common variants

As a separate approach, we used a recently developed method19 to estimate the total number of independent height-associated variants with effect sizes similar to the ones identified. We obtained this estimate using the distribution of effect sizes observed in Stage 2 and the power to detect an association in Stage 1, given these effect sizes (Supplementary Methods). The cumulative distribution of height loci, including those we identified and others as yet undetected, is shown in Figure 1b. We estimate that there are 697 loci (95% confidence interval (CI): 483-1040) with effects equal or greater than those identified, which together would explain approximately 15.7% of the phenotypic variation in height or 19.6% (95% CI: 16.2-25.6) of height heritability (Supplementary Table 4). We estimated that a sample size of 500,000 would detect 99.6% of these loci at P<5×10-8. This figure does not account for variants that have effect sizes smaller than those observed in the current study and, therefore, underestimates the contribution of undiscovered common loci to phenotypic variation.

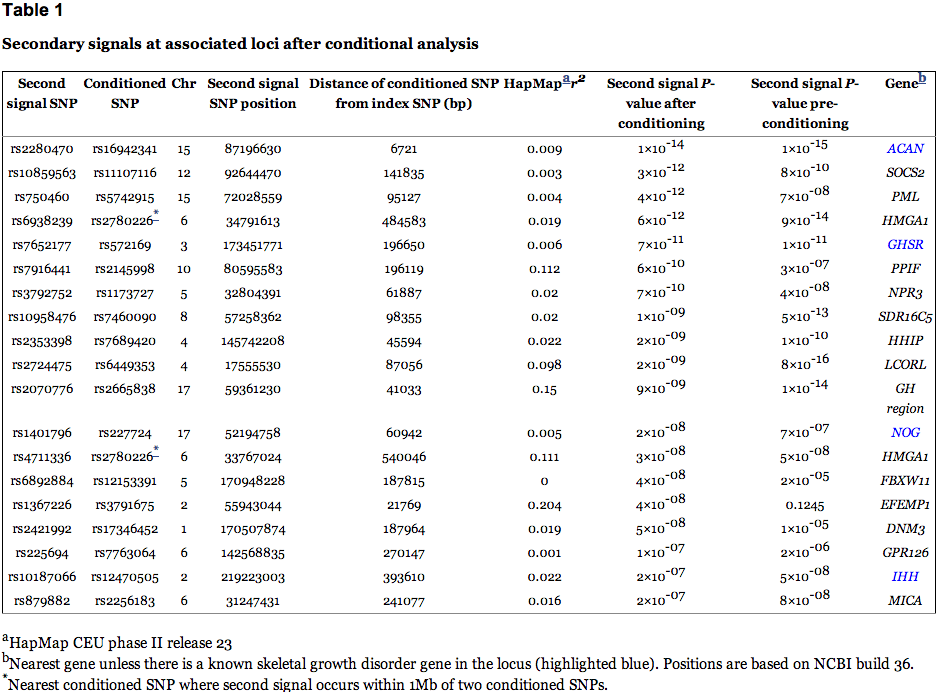

A further possible source of missing heritability is allelic heterogeneity – the presence of multiple, independent variants influencing a trait at the same locus. We performed genome-wide conditional analyses in a subset of Stage 1 studies, including a total of 106,336 individuals. Each study repeated the primary GWA analysis but additionally adjusted for SNPs representing the 180 loci associated atP<5×10-6 (Supplementary Methods). We then meta-analysed these studies in the same way as for the primary GWA study meta-analysis. Nineteen SNPs within the 180 loci were associated with height atP<3.3×10-7 (a Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold calculated from the ~15% of the genome covered by the conditioned 2Mb loci; Supplementary Methods, Table 1, Figure 2, Supplementary Figure 3). The distances of the second signals to the lead SNPs suggested that both are likely to be affecting the same gene, rather than being coincidentally in close proximity. At 17 of 17 loci (excluding two contiguous loci in the HMGA1 region), the second signal occurred within 500kb, rather than between 500kb and 1 Mb, of this lead SNP (binomial test P=2×10-5). Further analyses of allelic heterogeneity may identify additional variants that increase the proportion of variance explained. For example, within the 180 2Mb loci, a total of 45 independent SNPs reached P<1×10-5 when we would expect <2 by chance.

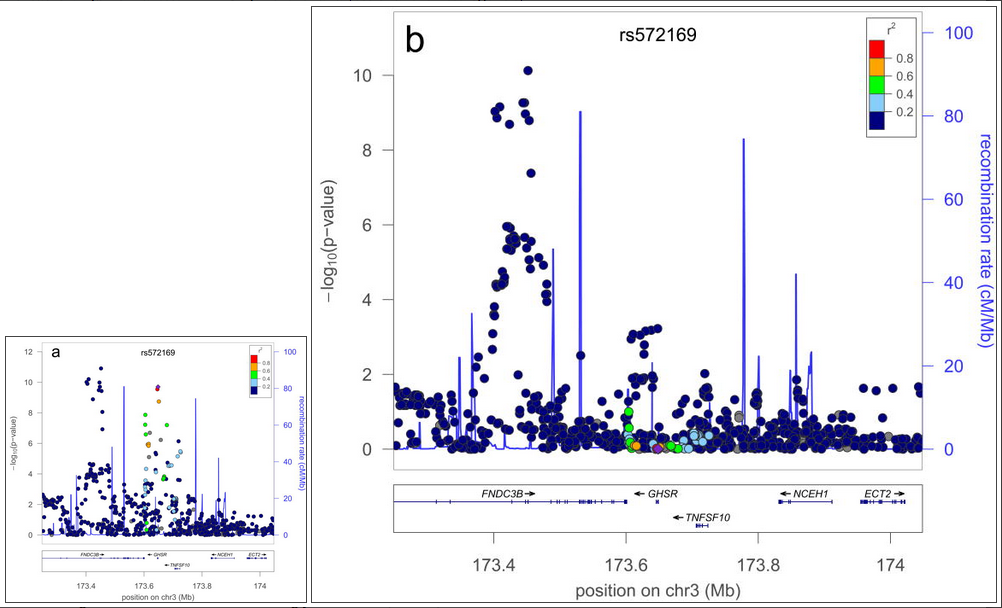

Secondary signals at associated loci after conditional analysis

Example of a locus with a secondary signal before (a) and after (b) conditioning

Whilst GWA studies have identified many variants robustly associated with common human diseases and traits, the biological significance of these variants, and the genes on which they act, is often unclear. We first tested the overlap between the 180 height-associated variants and two types of putatively functional variants, nonsynonymous (ns) SNPs and cis-eQTLs (variants strongly associated with expression of nearby genes). Height variants were 2.4-fold more likely to overlap with cis-eQTLs in lymphocytes than expected by chance (47 variants: P=4.7×10-11) (Supplementary Table 7) and 1.7-fold more likely to be closely correlated (r2≥0.8 in HapMap CEU) with nsSNPs (24 variants P=0.004) (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 8). Although the presence of a correlated eQTL or nsSNP at an individual locus does not establish the causality of any particular variant, this enrichment shows that common functional variants contribute to the causal variants at height-associated loci. We also noted five loci where the height associated variant was strongly correlated (r2>0.8) with variants associated with other traits and diseases (P<5×10-8), including bone mineral density, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, psoriasis and obesity, suggesting that these variants have pleiotropic effects on human phenotypes (Supplementary Methods; Supplementary Table 9).

We next addressed the extent to which height variants cluster near biologically relevant genes; specifically, genes mutated in human syndromes characterized by abnormal skeletal growth. We limited this analysis to the 652 genes occurring within the recombination hotspot-bounded regions surrounding each of the 180 index SNPs. We showed that the 180 loci associated with variation in normal height contained 21 of 241 genes (8.7%) found to underlie such syndromes (Supplementary Table 10), compared to a median of 8 (range 1-19) genes identified in 1,000 matched control sets of regions (P<0.001: 0 observations of 21 or more skeletal growth genes among 1,000 sets of matched SNPs). In 13 of these 21 loci the closest gene to the most associated height SNP in the region is the growth disorder gene, and in 9 of these cases, the most strongly associated height SNP is located within the growth disorder gene itself (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 11). These results suggest that GWA studies may provide more clues about the identity of the functional genes at each locus than previously suspected.

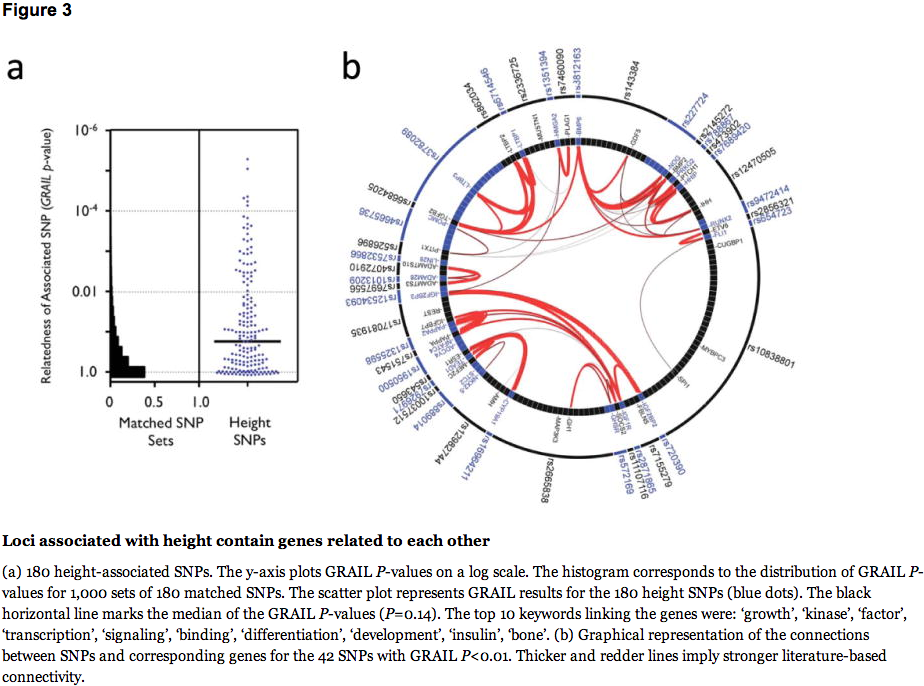

We also investigated whether significant and relevant biological connections exist between the genes within the 180 loci, using two different computational approaches. We used the GRAIL text-mining algorithm to search for connectivity between genes near the associated SNPs, based on existing literature20. Of the 180 loci, 42 contained genes that were connected by existing literature to genes in the other associated loci (the pair of connected genes appear in articles that share scientific terms more often than expected at P<0.01). For comparison, when we used GRAIL to score 1,000 sets of 180 SNPs not associated with height (but matched for number of nearby genes, gene proximity, and allele frequency), we only observed 16 sets with 42 or more loci with a connectivity P<0.01, thus providing strong statistical evidence that the height loci are functionally related (P=0.016) (Figure 3a). For the 42 regions with GRAIL connectivity P<0.01, the implicated genes and SNPs are highlighted in Figure 3b. The most strongly connected genes include those in the Hedgehog, TGF-beta, and growth hormone pathways.

Loci associated with height contain genes related to each other

As a second approach to find biological connections, we applied a novel implementation of gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (Meta-Analysis Gene-set Enrichment of variaNT Associations, MAGENTA21) to perform pathway analysis (Supplementary Methods). This analysis revealed 17 different biological pathways and 14 molecular functions nominally enriched (P<0.05) for associated genes, many of which lie within the validated height loci. These gene-sets include previously reported11,13 (e.g. Hedgehog signaling) and novel (e.g. TGF-beta signaling, histones, and growth and development-related) pathways and molecular functions (Supplementary Table 12). Several SNPs near genes in these pathways narrowly missed genome-wide significance, suggesting that these pathways likely contain additional associated variants. These results provide complementary evidence for some of the genes and pathways highlighted in the GRAIL analysis. For instance, genes such as TGFB2 andLTBP1-3 highlight a role for the TGF-beta signaling pathway in regulating human height, consistent with the implication of this pathway in Marfan syndrome22.

Finally, to examine the evidence for the potential involvement of specific genes at individual loci, we aggregated evidence from our data (eQTLs, proximity to the associated variant, pathway-based analyses), and human and mouse genetic databases (Supplementary Table 13). Of 32 genes with highly correlated (r2>0.8) nsSNPs, several are newly identified strong candidates for playing a role in human growth. Some are in pathways enriched in our study (such as ECM2, implicated in extracellular matrix), while others have similar functions to known growth-related genes, including FGFR4 (FGFR3 underlies several classic skeletal dysplasias23) and STAT2 (STAT5B mutations cause growth defects in humans24). Interestingly, Fgfr4-/- Fgfr3-/- mice show severe growth retardation not seen in either single mutant25, suggesting that the FGFR4 variant might modify FGFR3-mediated skeletal dysplasias. Other genes at associated loci, such as NPPC and NPR3 (encoding the C-type natriuretic peptide and its receptor), influence skeletal growth in mice and will likely also influence human growth17. Many of the remaining 180 loci have no genes with obvious connections to growth biology, but at some our data provide modest supporting evidence for particular genes, including C3orf63, PML, CCDC91, ZNFX1, ID4, RYBP, SEPT2,ANKRD13B, FOLH1, LRRC37B, MFAP2, SLBP, SOCS5, and ZBTB24 (Supplementary Table 13).

We have identified >100 novel loci that influence the classic polygenic trait of normal variation in human height, bringing the total to 180. Our results have potential general implications for genetic studies of complex traits. We show that loci identified by GWA studies highlight relevant genes: the 180 loci associated with height are non-randomly clustered within biologically relevant pathways and are enriched for genes that are involved in growth-related processes, that underlie syndromes of abnormal skeletal growth, and that are directly relevant to growth-modulating therapies (GH1, IGF1R, CYP19A1,ESR1). The large number of loci with clearly relevant genes suggests that the remaining loci could provide potential clues to important and novel biology.

We provide the strongest evidence yet that the causal gene will often be located near the most strongly associated DNA sequence variant. At the 21 loci containing a known growth disorder gene, that gene was on average 81 kb from the associated variant, and in over half of the loci it was the closest gene to the associated variant. Despite recent doubts about the benefits of GWA studies26, this finding suggests that GWA studies are useful mapping tools to highlight genes that merit further study. The presence of multiple variants within associated loci could help localize the relevant genes within these loci.

By increasing our sample size to >100,000 individuals, we identified common variants that account for approximately 10% of phenotypic variation. Although larger than predicted by some models26, this figure suggests that GWA studies, as currently implemented, will not explain a majority of the estimated 80% contribution of genetic factors to variation in height. This conclusion supports the idea that biological insights, rather than predictive power, will be the main outcome of this initial wave of GWA studies, and that new approaches, which could include sequencing studies or GWA studies targeting variants of lower frequency, will be needed to account for more of the “missing” heritability. Our finding that many loci exhibit allelic heterogeneity suggests that many as yet unidentified causal variants, including common variants, will map to the loci already identified in GWA studies, and that the fraction of causal loci that have been identified could be substantially greater than the fraction of causal variantsthat have been identified.

In our study, many associated variants are tightly correlated with common nsSNPs, which would not be expected if these associated common variants were proxies for collections of rare causal variants, as has been proposed27. Although a substantial contribution to heritability by less common and/or quite rare variants may be more plausible, our data are not inconsistent with the recent suggestion28 that a large number of common variants of very small effect mostly explain the regulation of height.

In summary, our findings indicate that additional approaches, including those aimed at less common variants, will likely be needed to dissect more completely the genetic component to complex human traits. Our results also strongly demonstrate that GWA studies can identify large numbers of loci that together implicate biologically relevant pathways and mechanisms. We envision that thorough exploration of the genes at associated loci through additional genetic, functional, and computational studies will lead to novel insights into human height and other polygenic traits and diseases.

Methods summary

The primary meta-analysis (Stage 1) included 46 GWA studies of 133,653 individuals. The in-silico follow up (Stage 2) included 15 studies of 50,074 individuals. All individuals were of European ancestry and >99.8% were adults. Details of genotyping, quality control, and imputation methods of each study are given in Supplementary Methods Table 1-2. Each study provided summary results of a linear regression of age-adjusted, within-sex Z scores of height against the imputed SNPs, and an inverse-variance meta-analysis was performed in METAL (http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/METAL/). Validation of selected SNPs was performed through direct genotyping in an extreme height panel (N=3,190) using Sequenom iPLeX, and in 492 Stage 1 samples using the KASPar SNP System. Family-based testing was performed using QFAM, a linear regression-based approach that uses permutation to account for dependency between related individuals29, and FBAT, which uses a linear combination of offspring genotypes and traits to determine the test statistic30. We used a previously described method to estimate the amount of genetic variance explained by the nominally associated loci (using significance threshold increments from P<5×10-8 to P<0.05)18. To predict the number of height susceptibility loci, we took the height loci that reached a significance level of P<5×10-8 in Stage 1 and estimated the number of height loci that are likely to exist based on the distribution of their effect sizes observed in Stage 2 and the power to detect their association in Stage 1. Gene-by-gene interaction, dominant, recessive and conditional analyses are described in Supplementary Methods. Empirical assessment of enrichment for coding SNPs used permutations of random sets of SNPs matched to the 180 height-associated SNPs on the number of nearby genes, gene proximity, and minor allele frequency. GRAIL and GSEA methods have been described previously20,21. To assess possible enrichment for genes known to be mutated in severe growth defects, we identified such genes in the OMIM database (Supplementary Table 10), and evaluated the extent of their overlap with the 180 height-associated regions through comparisons with 1000 random sets of regions with similar gene content (±10%).

The Kulkarni family can only ride scooters and wears custom made clothes and shoes

The Kulkarni family can only ride scooters and wears custom made clothes and shoes The Kulkarni family: Sharad (right) and his wife Sanjot (second left) and their daughters Sanya (left) and Mruga (right) stand a combined 26ft tall

The Kulkarni family: Sharad (right) and his wife Sanjot (second left) and their daughters Sanya (left) and Mruga (right) stand a combined 26ft tall Walking tall: Mruga (second from right) and her sister Sanya (right) tower above their friends

Walking tall: Mruga (second from right) and her sister Sanya (right) tower above their friends On the move: Mr Kulkarni travels around on a scooter because he is too tall to use public transport comfortably

On the move: Mr Kulkarni travels around on a scooter because he is too tall to use public transport comfortably India’s tallest couple: Mr Kulkarni stands at 7ft 1.5in and his wife Sanjot at 6ft 2.6in

India’s tallest couple: Mr Kulkarni stands at 7ft 1.5in and his wife Sanjot at 6ft 2.6in Both Sanya and Mruga want to be models and hope that their height could give them a huge advantage in the industry

Both Sanya and Mruga want to be models and hope that their height could give them a huge advantage in the industry

0

0